PANS/PANDAS RESOURCES and ARTICLES

FAQ’s

-

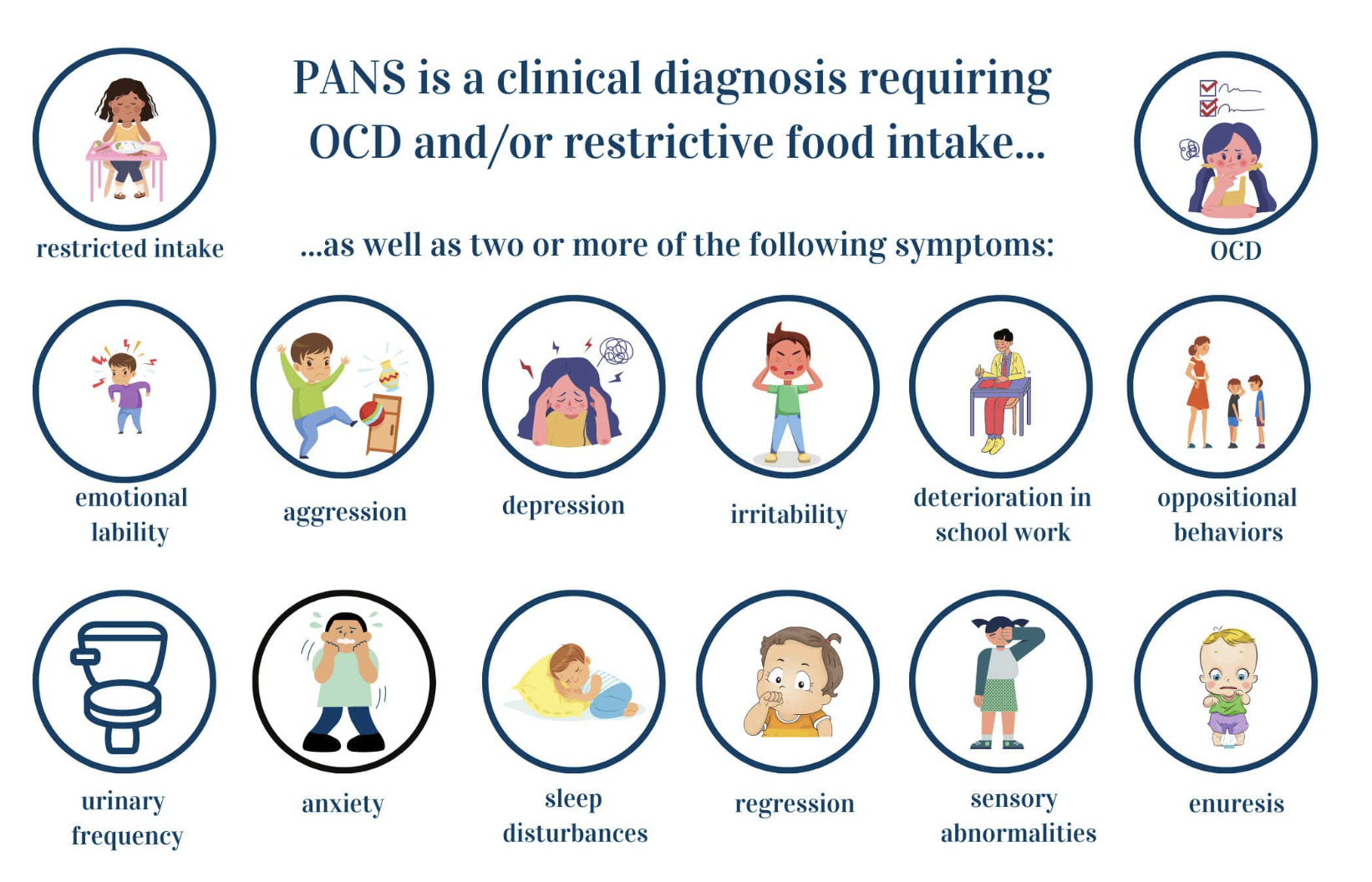

PANS (Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome) and PANDAS (Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infections) are conditions in which a child’s immune system mistakenly triggers inflammation against the brain, following an infection. This autoimmune response can lead to a sudden onset of symptoms such as anxiety, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, mood changes, tics, sleep disturbances, and cognitive or behavioral regression.

The term PANDAS is used when the triggering infection is streptococcal. In many children, however, immune activation may be triggered by other infections or inflammatory stressors, which fall under the broader PANS diagnosis. Commonly implicated contributors include infections such as Borrelia (Lyme disease), Bartonella, Babesia, and Mycoplasma. Environmental factors such as mold exposure can also worsen inflammation and symptom severity. Some children who initially develop PANDAS may later experience symptom flares triggered by other infections or immune stressors, fitting the broader PANS picture.

These conditions are not psychiatric in origin, but rather immune-mediated. Treatment focuses on identifying and addressing underlying infections and inflammation, supporting immune regulation, and promoting nervous system healing and recovery.

-

Commonly reported symptoms include sudden onset anxiety, OCD behaviors, motor changes, sleep disturbances, sensory sensitivity, food restriction and school performance changes — symptoms that can resemble other conditions and should be evaluated carefully.

The abrupt nature of these changes is often what alerts families that “something isn’t right.”

-

Standard medical evaluations — including MRIs, spinal taps, and routine lab work — are frequently normal.

As a result, children are often referred primarily to psychiatry, where treatment focuses on symptom management rather than immune drivers and root cause of illness.While psychiatric support can be helpful, it does not address the underlying cause of PANS/PANDAS.

-

PANS/PANDAS is rarely caused by a single factor. Most children improve when care addresses:

The pathogen load (targeting infections)

The inflammatory burden

Immune system dysregulation (stopping the body from attacking itself, even after infections have been suppressed)

Stress physiology and nervous system regulation, for both patients and their caregivers

Nutrition and detoxification

Healing is not always linear. My role is to help families make sense of what is happening, create a clear plan, and adjust that plan as the child responds.

FAQ’s for parents ❤️

-

Listen to your gut! Parents are rarely wrong. If you identify with any of the symptoms being mentioned above, get your child a PANS/PANDAS workup as soon as possible. If you don’t feel comfortable with your first visit, get a second opinion.

-

PANS/PANDAS is often triggered by an immune stressor such as an infection or inflammatory exposure. In susceptible children, this immune response can lead to abrupt changes in mood, behavior, and cognition — which is why parents often describe a sudden “before and after.”

-

No. While stress can worsen symptoms and autoimmunity, it is not the cause. Parents do not cause PANS/PANDAS. These conditions reflect biologic immune responses, not family dynamics or parenting styles.

-

Routine imaging and labs are often normal in PANS/PANDAS. These conditions involve functional inflammation and immune signaling, which may not appear on conventional testing. A normal MRI or spinal tap does not rule this out.

-

Treatment is individualized, but often includes:

Identifying and addressing infectious triggers

Supporting nervous system regulation

Supporting the autoimmune response triggered by infectious triggers

Reducing inflammatory burden

Supporting nutrition and detox pathways

Thoughtful use of medications or supplements when appropriate

Ongoing reassessment as the child responds

There is no single protocol that works for every child.

-

Children can benefit from the right psychiatric and therapeutic support during acute and recovery phases. These interventions can be an important part of a multidisciplinary plan even while the immune and neurological contributors are being addressed. However, psychiatric medications alone do not address the underlying immune drivers, and in some cases may make things worse. Individualized care and management is essential. Support is most effective when medical, neurologic, and emotional support are thoughtfully integrated.

-

Some children improve over time, especially with early recognition and support. Others require longer-term management. The goal of care is to stabilize the immune system, reduce inflammation, and support healthy brain function so development can continue.

-

First, what you are going through is extraordinarily hard and often very traumatic. I am so sorry you have found yourself here. I am here to help if I can help your child medically or help you directly. My appointments with parents often involve helping them sort through the experience they are navigating with other providers, and educating them (and empowering them) on the process.

I am glad to say that there are now many support groups online that are both supportive and educational, many through Facebook and the resources listed below.

xxx

ADDITIONAL EDUCATION/ RESOURCES

NEUROIMMUNE FOUNDATION - Symptoms and Diagnosis

PANDAS NETWORK - Clinician Directory

Autoimmunity and PANS/PANDAS, Autoimmune Institute

PANDAS/PANS for Beginners, Masterclass by Jill Crista

Diagnostic Flowchart and Treatment Guidelines; PANDAS Physicians Network

BOOKS

Demystifying PANS/PANDAS: A Functional Medicine Desktop Reference on Basal Ganglia Encephalitis, by Nancy O’Hara

A Light in the Dark for PANDAS and PANS, by Jill Crista

Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness; by Sasannah Cahalan

WHY YOU ARE STILL SICK: How infections can break your immune system & How you can recover; by Gary Kaplan

ARTICLES

How A Common Throat Infection Can Rewire Children’s Brains, BBC

9 Year Old with Acute Changes Overnight, People Magazine

Most parents I know, struggling to support a child with PANS/ PANDAS can recall with heartbreaking clarity the exact day they lost their child to this disease. Awareness and quick intervention is key.

PANDAS remains one of the most devastating conditions I have ever come across in medicine, both for the patient and also the family. Confusion, fear, scrutiny and isolation are too common for families navigating this diagnosis. My hope here is to provide resources and education so that other children and families can get quick help. I also want to be a resource to frightened parents, unsure of how to support their child, and also themselves during such a scary time.

If a child is one way one day, and another way the next day without an obvious source of trauma, PLEASE ensure that child gets a full workup with a PANS/PANDAS literate clinician. And quickly.

Our very personal journey with PANS/PANDAS (and the WHY behind what I do) …

When my son Jack was nine years old, his joyful, playful personality changed dramatically over the course of just a few days. We had just finished a happy holiday season and were preparing for a trip to Utah—one of his favorite places—when subtle symptoms first appeared: a small tic and a tremor in his hands. Within days, more alarming changes followed. A football agility ladder he received for Christmas began to consume him in a way that felt entirely out of his control. He would repeat drills compulsively, over and over, until he collapsed on the ground in tears from physical exhaustion.

As the days passed—peaking during our flight—his symptoms escalated rapidly. I’ve often described it as if our sweet kid was caught in an invisible tornado. He was literally begging for help from something none of us understood. The weeks that followed were marked by constant distress: prolonged episodes of crying and wailing, inability to sleep or eat, dilated pupils, relentless agitation, and a look of fear that was heartbreaking to witness.

During this time, Jack was diagnosed and treated for strep throat. Regrettably, no connection was made at the time between the infection and his sudden neuropsychiatric decline—what we now understand to be PANDAS. When school resumed, his teachers later described that period as “the time the light went out in him.” Once a confident, engaged leader in the classroom, he became withdrawn and quiet, sitting in the back of the room as his academic performance deteriorated. He could no longer tolerate being at home with sitters he loved, nor participate in most after-school activities on a consistent basis. He became increasingly disconnected from the world around him.

Over the following months, Jack was diagnosed with “acute OCD” and referred to therapy, which we navigated with commitment, confusion and little improvement. Psychiatry suggested institutionalization—an unimaginable recommendation for an otherwise healthy and happy child—while repeated appointments left us feeling dismissed. Although subtle symptoms lingered in the years ahead, his most severe symptoms slowly eased over the next few months, and life resumed in a different form. We brought in ongoing therapy, academic support and tutoring, and tried multiple medications for what had evolved into symptoms of depression, anxiety, OCD, and ADHD. None provided meaningful or lasting relief. Life went on, and we watched him closely for signs of recurrence.

Five years later, while on a family trip to Las Vegas, Jack looked at me during our walk back to the hotel and said quietly, “Mom, something isn’t right.” He had recently recovered from a mild case of COVID and otherwise seemed well.

In the days ahead, he began experiencing night sweats, blurry vision, and the return of his tremor. Soon after, he developed profound derealization and what we would later learn was Alice in Wonderland syndrome—a distortion of visual perception that left him disoriented. His OCD flared intensely. Brain fog, anxiety, and insomnia became barriers to a successful academic day. At times he would slip into near-catatonic states, unable to pull himself out of them.

MRIs and spinal taps were normal. Lab work was repeated again and again, giving us helpful clues but no slam dunk answer. We consulted dozens of specialists across the country—each offering helpful theories and tips, none offering complete answers. Every appointment felt like another puzzle piece or two placed on the table, yet the full picture remained elusive. Psychiatry recommended antidepressants, which only worsened his symptoms. Eventually, we were told there were few remaining options. We pulled him out of school, realizing there was no appropriate support for what he was experiencing.

We didn’t need a psychiatric ward. We didn’t need behavioral modification. Jack had never been defiant or troubled—he was a sensitive, thoughtful child in a body under attack. But the conventional system had no framework for what was happening, and little time to look deeper. The care we encountered, though often well-intentioned, became its own source of trauma.

As his symptoms continued, therapists and educational consultants began strongly advocating for an intensive wilderness program. Jack’s history—multiple moves, family transitions, and accumulated stress—made the picture appear psychosocial. Reluctantly, and with limited alternatives, we agreed. He spent three months in the wilderness. While he did gain some tools for managing anxiety and OCD, it was ultimately a traumatic experience for a child who never needed behavioral correction—he needed medical answers.

Just before he left, one perceptive clinician asked a simple question: “Does he have any strange new rashes?” I mentioned the new red markings on his back that I hadn’t fully connected to the bigger picture. She suggested testing for Bartonella, an infection often transmitted by ticks that can cause significant neuropsychiatric symptoms and a rash that looks like scratch marks on the back. Those results came back while Jack was away—positive for Bartonella, Babesia, and Borrelia (Lyme), all tick borne diseases. All were culprits of the symptom collection he had, and all drivers of brain inflammation. For the first time, we had a unifying explanation: neuroinflammation driven by tick-borne infections, likely triggered or amplified by the immune modulating effects of COVID.

The year that followed became a deep and deliberate process of identifying and treating the drivers of his inflammation—tick-borne infections, mold exposure, mycoplasma, and immune dysregulation. Equally important was addressing the nervous system injury and trauma that had accumulated from years of being misunderstood and untreated. Healing has not been linear, but it has been real.

For all of us, the journey continues. Supporting Jack’s recovery—and our own—has required patience, persistence, and self compassion. The trauma of fighting for answers and loosing friends who don’t understand along the way does not simply disappear, but understanding what truly happened has allowed us to move forward with clarity, purpose, and hope.

This last year for Jack has been one of re-entry; back into high school and back into his favorite sport, basketball. He remains the kindest and most resilient kid I know, working his way back to graduate on time with his peers and pursue his dreams of playing hoops in college.

This story illustrates one family’s experience, not a treatment guide. The information provided on this page is for educational purposes only and is not intended to diagnose, treat, or replace individualized medical care.